| One of the best experiences I had in my teaching career was the FMF program. |  |

| One of the best experiences I had in my teaching career was the FMF program. |  |

For more pictures go to

|

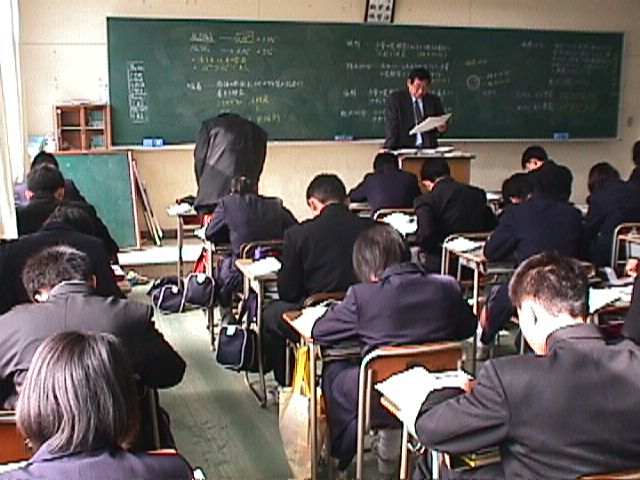

We are truly becoming one world. The Internet is going to connect us all and TV is doing the same thing, but the only way to really know about another culture is to go and experience it for yourself. It puts culture in a meaningful perspective. I recall entering a Japanese classroom with a local teacher. The uniformed students- roughly 40 in a class – rose in unison and bowed to greet their instructor. "Please teach us today," they said. If American parents perceive school as an important place, a place of learning, they’ll put value on education as the Japanese do. If parents believe strongly in education, they’ll sit down and work with the kids on their homework. Then the kids are going to realize that education is important. In America, students and parent seem to think it takes talent to do well in science, where in Japan, they feel that hard work is how to succeed. I feel this is the answer to many problems our students have in school- they simply do not spend enough time on task to do well. If you want to be good at anything, you have to practice. Anyway if you are interested in this program read the following: |

Year 2001 Fulbright Memorial Fund Teacher Program

The Fulbright Memorial Fund Teacher Program (FMF) is an opportunity for U.S. primary and secondary teachers and administrators to participate in a three-week study visit to Japan. The program, which is fully funded by the Government of Japan, aims to increase the level of understanding between Japan and the United States and to provide a significant opportunity for the professional development of educators.

Applicants must be U.S. citizens who are employed full-time in any discipline as a teacher or administrator for grades 1 through 12. Individuals complete an application, including a two-part essay describing a follow-on plan for imparting the knowledge gained through the experience to their classrooms, schools, and communities. Two letters of reference as well as the approval of the applicant’s supervisor are required.

The program in Japan includes an orientation and introduction in Tokyo. Participants then travel in small groups to prefectures outside Tokyo to visit local schools, interact with teachers and students, and to meet local and regional government and industry officials. Included is a weekend homestay with a Japanese host family. The program concludes in Tokyo before traveling home to the U.S.

Teachers and administrators from all areas of the U.S. primary and secondary educational sector are encouraged to submit applications for the year 2001 cycles of the Fullbright Memorial Fund Teacher Program. We expect another 600 award recipients this year. Interested individuals may request a year 2001 application packet by calling the Institute of International Education at 1-888-527-2636 or by visiting our website at www.iie.org/pgms/fmf.

The application deadline is December 2001.

Dr. Esaki a Nobel Prize winner in physics spoke in Chicago at the Japan America Society of Chicago luncheon I attended. He is Chairman of the Japanese National Commission on Educational Reform, and President, Shibaura Institute of Technology. His speech, "Meeting the Challenge of the Information Age: Educational Reform in Japan," can be found on the Japan America Society website

www.us-japan.org/jascOr at:

http://www.us-japan.org/jasc/no_frames/members/calendar/esaki.aspIt has implications for the U.S. education system. It is interesting to see what he preceives to be problems with Japan’s education system compared to ours.

If the above sites are no longer valid you can download a Microsoft Word file of his talk.

Click here to get the word file.

LINKS SOME ONE SENT ME THAT MAY BE OF INTEREST, IF THEY ARE STILL ACTIVE.

1.The Daily Yomiuri Newspaper on line: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/index-e.htmTHE FOLLOWING COMES FROM SEVERAL GUIDE BOOKS I READ. I WOULD TELL YOU WHICH IF I COULD REMEMBER.

The Group

One of the most widely disseminated ideas regarding the Japanese is the importance of the group over the individual. The image of loyal company workers bellowing out the company anthem and attending collective exercise sessions has become a motif that is almost as powerful as Mt. Fuji in calling to mind the Land of the Rising Sun.

It’s easy to fall into the spirit of these kinds of images and start seeing the business-suited crowds jostling on the Yamanote line as so many ant-like members of a collectivised society that has rigorously suppressed individual tendencies. If this starts to happen, it’s useful to remember that in some senses the Japanese are no less individual than their Western counterparts. The Japanese are not robotic clones, they experience many of the same frustrations and joys as the average Westerner and, given the opportunity, many will complain about their work conditions, the way their boss treats them and so on, just like any Westerner. The difference is, that while these individual concerns have a place in the lives of the Japanese, their principal orientation remains that of the group. The Japanese do not see their individual differences as defining.

For the Japanese, the individual has its rights and interests, but in the final analysis, these are subsumed under the interests of the group. Indeed the tension between group and individual interests and the inevitable sacrifices demanded of the latter has been a rich source for Japanese art. The Japanese see the tension as one between honne, the individual’s personal views, and tatemae, the views that are demanded by the individual’s position in the group. The same difference is expressed in the terms ninjo, which translates loosely as ‘human feelings’ or, looser still, as the ‘dictates of the heart’, and giri, which is the individual’s social obligations. The salaryman who spends long hours at the office away from the family he loves is giving priority to giri over ninjo.

The precedence of the group is so important that it cannot be stressed too much in understanding Japanese culture. Among other things, it gives rise to the important uchi (inside) and soto (outside) distinction. For the Japanese all things are either inside or outside. Relationships, for example, are generally restricted to those inside the groups to which they belong. Mr. Sato, who works with Nissan, will have a social life comprised entirely of fellow Nissan workers and family. Mrs. Sato, if she doesn’t work (which is likely), will mix with members of the tea ceremony and jazz ballet clubs to which she belongs.

The whole of Japanese social life is an intricate network of these inside-outside distinctions. Of course, this is hardly unique to Japan; it’s just that in Japan being inside a group makes such special demands on the individual. Perhaps foreigners who have spent many years in Japan learning the language and who finally throw up their hands in despair, complaining ‘you just can’t get inside this culture’, should remember that to be ‘inside’ in Japan is to surrender the self to the priorities of the group - and not many foreigners are willing or able to do that.

Men & Women

Japan may be a modern society in many respects, but don’t expect the same level of equality between the genders that you have come to expect in your own country. As everything else in Japan male-female roles and relationships are strictly codified. Although there’s some evidence that this is changing, it’s definitely doing so at a much slower pace than it has done in the West. Part of the reason is that ‘feminism’ is a Western import and in a Japanese context tends to have a different resonance than it does in its culture of origin. Even the word ‘feminist’ has been co-opted so that a Japanese male can proudly declaim himself a femunisuto when he means that he is the kind of man that treats a woman as a ‘lady’, in the Walter Raleigh sense.

Anyone who visits Japan will be struck by the fact that Japanese women, like women in other parts of the world, are subordinate to men in public life. However, both sexes have their spheres of influence, domains in which they wield power. Basically women are uchi-no (of the inside) and men are soto-no (of the outside). That is, the woman’s domain is the home, and here she will take care of all decisions related to the daily running of domestic affairs. The husband, on the other hand, while he may be the breadwinner, will still hand over his pay packet to his wife, who will then allocate the money according to domestic expenses and provide the husband with an allowance for his daily needs.

In public life, however, it is the men who rule supreme. In this world it is the role of women to listen, to cater to male needs and often to serve as vents for male frustrations. As any Western woman who tries hostessing will discover, women are expected to help men bear the burden of their public-life responsibilities not by offering advice - that would be presumptuous in the extreme - but by listening and making the appropriate sympathetic noises at the right moments.

Switch on a Japanese TV and you will se the same male-female dynamic at work. The male host invariably has a female shadow whose job is to agree with everything he says, make astonished gasps at his erudition and to giggle politely behind a raised hand at his off-the-cuff witty remarks. These so desu girls, as they’re known, are a common feature of countless aspects of Japanese daily life. It’s de riguer for all companies to employ a bevy of nubile OLs, or ‘office ladies’, who’s tasks include chiming a chorus of falsetto ‘welcomes’ to visitors, making cups of tea and generally adding a personal touch to an otherwise stolid male atmosphere.

Unfortunately, for many Japanese women, this is the sum of their job prospects. To make matters worse, it is considered that by the age of 25 they should be married, and in Japan married women are expected to resign from their work. This cut-off point of 25 years is a very serious one. Women who remain unmarried after this age are frequently alluded to as ‘Christmas cake’, this being a useless commodity after the 25th. By the time a woman is 26 and up, she will be regarded with suspicion y many men, who will wonder whether there isn’t some flaw in her character that has prevented her from being swallowed up by the marriage market earlier.

Perhaps most disturbing for Western women visiting Japan, is the way in which women feature in so much of the male-oriented mass culture. It’s not so much women being depicted as sex objects, which most Western women would at least be accustomed to in their own countries, but the fact that in comic strips, magazines and movies, women are so often shown being brutalized, passive victims in bizarre, sado-masochistic rites. Some disturbing conclusions could be drawn from much of the output of the Japanese media - at the very least it could be said that popular Japanese male sexuality has a very sadistic edge to it.

While these fantasies are disturbing, it is possible to take refuge in the thought that they are fantasies, and women are in fact a great deal safer in Japan than they are in other parts of the world. Harassment, when it does occur, is usually furtive, occurring in crowded areas such as trains; however, with direct confrontation, almost all Japanese men will be shamed into withdrawing the groping hand.

Education

Among the many things that surprise visitors to Japan is the leniency with which very young children are treated. Volumes have been written on this subject and the general consensus would seem to be that the Japanese see the early years of childhood as a kind of blissful Eden, a period of gloriously spoiled dependency that prefaces the harsh socialization of the Japanese education system.

At an age as young as three or four, however, the party is over: children then enter the nurseries that start preparing them for one of the most grueling education systems in the world. Competition is fierce from the beginning, since getting into the right school initially can meanan important head start when it comes to the university exams. These exams, of legendary difficulty, are so demanding that any student preparing for them and getting more than four hours sleep a night, is said to have no hope of passing.

To help coach students through the exams, evening schools have sprung up and are often more successful in teaching the school curriculum than the schools themselves. Students who fail to gain entry to the university of their choice frequently spend one or two years repeating the final year of school and sitting the exams again. These students, known as ronin, or ‘masterless samurai’, are in a kind of limbo between the school education system and the higher education system, the key to employment in Japan.

The intense pressure of this system derives in no small part from the fact that 12 years of education culminates in just two examinations that effectively determine the future of the examinee. One exam is sat by all Japanese final-year high school students on the same day; the other exam is specific to the university the student wishes to attend.

Once exams have been completed and a student gains a university place, it is time to let loose a little. Basically, university or college is considered a transitional stage between the world of education and employment, a stage in which one spends more time in drinking bouts with fellow students than in the halls of higher learning. In a sense the university years, for those who make it, are similar to the early years of childhood Al kinds of antics are looked upon indulgently as the excesses of youth. Some have seen a pattern in this - an alternation between extreme pressure and almost complete relaxation - which is mirrored in many aspects of Japanese social life.

As in other parts of the world, the Japanese education system processes male and female students differently. The top universities are dominated by male students, with many female students opting for two-year college courses, often in topics seen as useful training for family life, such as child psychology.

According to one traveler, the best way to gain an understanding of the Japanese education system is to actually visit a school:

"I think it is a good idea to pay a visit to an elementary or high

school. It will tell you a great deal about Japanese society and you might et a

chance to tell the students about your own country. You’ll be a hit!"

Company life is very different for men and women. For men it is a lifetime commitment that will take up far more of their waking hours than will their family. For women, company-life experience is liable to be limited to four or five years of answering the phone and offering tea to visitors before retreating to a life of domesticity. Women who return to work after marriage, and more and more are doing so, are likely to be involved in small-scale industry that provides none of the benefits available for most Japanese workers. The gap between average female earnings and average male earnings is greater in Japan than any comparable advanced nation.

For the Japanese themselves, the issue is a difficult one. After all, Japanese companies make such excessive demands on their workers that many Japanese women have no desire to share the responsibilities that are, at present, almost entirely undertaken by men. Company life for most men is a non-stop commitment from graduation to retirement. Even their annual two-weeks holidays are often forfeited because it would look like disloyalty to want to have a holiday from the company.

Peter Tasker, in his book Inside Japan (Penguin, 1987), points to the story of the Bureau for the Promotion of the Forty Hour Week; so enormous was their task of persuading Japanese corporations to change their work practices, that members of the bureau were forced to put in long hours of overtime and weekend work. Before too long their efforts came to the attention of authorities, who were unhesitating in praising them for their devotion for such a just cause.

Toilets

Western toilets are on the increase in Japan. On one trip aboard the bullet train, I was intrigued to see queues outside the Western toilet whilst the Japanese one remained vacant. A Dutch couple told me that back in the 70’s, there were instructive diagram diagrams on the correct use of western toilets as part of a drive to dissuade toilet-goers from standing on the seat and aiming from on high.

It’s quite common to see men urinating in public, typically in the evening in a bar district. In Shinjuku (tokyo) I watched a tipsy, soberly suited salaryman slip behind a policeman and pee against the wall a couple of feet behind him. When the salaryman was finished, he turned round, thanked the policeman, exchanged bows and tottered into the station.

Japanese toilets are Asian style- level with or in the floor. The correct position is to squat facing the hood, away from the door. This is the opposition to squat toilets in most other places in Asia. Make sure the contents of your pockets don’t spill out. Toilets paper isn’t always provided so carry tissues with you. Separate toilet slippers are often provided just inside the toilet door. These are for use in the toilet only, so remember to change out of them when you leave.

Mixed toilets also exist. Men and women often go through separately marked entrances, but land up in the same place. No-one feels worried and privacy is provided by cubicles and women are supposed to simply ignore the backs turned to them at the urinals.

A recent newspaper article claimed that in about four years, research on the " intelligent lavatory" would be complete. According to the article, these lavatories will use the latest microchip technology to check the user’s waste products, weight, temperature and even blood pressure. Further research will also investigate the possibility of direct links between these smart conveniences and the closest hospitals so that suspicious symptoms are reported instantly and nipped in the bud. Of course, there are wide implications in this merging of private moments and public data. Perhaps, in the realms of litigation, constipation will be considered as the withholding of information!

RYOKAN

Staying at a Ryokan. On arrival at the ryokan, you leave your shoes at the enterence steps, don a pair of slippers, and are shown by a maid to your room which has a tatamimat floor. Slippers are taken off before entering tatami rooms. Instead of using numbers, rooms are named after auspicious flowers, plants or trees.

The interior of the room will contain an alcove (tokonoma), probably decorated with a flower display or a calligraphy scroll. One side of the rooom will contain a cupboard with sliding doors for the bedding; the other side will have slididng screens ffcovered with rice paper and perhaps open onto a ceranda with a garden view.;

The room maid then serves tea with a sweet on a low table surrounded by cushions (zabuton) in the center of the room. At the same time you are asked to sign the register. A tray is provided with a towel, cotton robe (yukata) and a belt (obi) which you pit on before taking your bath. Remember to wear the left side over the right-the reverse order is used for dressing the dead. In colder weather, there will also be an outer jacket (tanzen). Your clothes can be put away in a closet or left on a hanger.

Dressed in your yukata, you will be shown to the bath (o-furo). At some ryokan, there are rooms with private baths, but the communal ones are often designed with ‘natural’ pools or a window looking out into a garden. Bathing is communal, but sexes are segregated. Make sure you can differentiate between the bathroom signs for men and women-see the Aside before this section-although ryokan used to catering for foreigners will often have signs in English. Many inns will have family bathrooms for couples or families.

Dressed in your yukaata after your bath, you return to your room where the maid will have laid out dinner-in some ryokan, dinner is provided is a separate room but you still wear your yukata for dining. Dinner usually includes standard dishes such as miso soup, pickles (tsukemono), vegetables in vinegar (sunomono), hors d’oeuvres (zensai), fish-either grilled or raw (sashimi), and perhaps tempura and a stew. There will also be bowls for rice, dips and sauces. Depending on the price, meals at a ryokan can become flamboyant displays of local cuisine or refined arrangements of kaiseki (a cuisinewhich obeys strict rules of form and etiquette for every detail of the mean and setting).

After dinner, whilst you are pottering around or not for a stroll admiring the garden, the maid will clear the dishes and prepare your bedding. A mattress is placed on the tatami floor and a quilt put on top. In colder weather, you can also add a blanket (mofu).

In the morning, the maid will knock to make sure you are awake and then come in to put away the bedding before serving breakfast-sometimes this is served in a separate room. Breakfast usually consists of pickles, dried seaweeed (nori), raw egg, dried fish, miso soup and rice. It can take a while for foreign stomachs to accept this novel fare early in the morning.

The Japanese tendency is to make the procedure at a ryokan seem rather rarefied for foreign comprehension and some ryokan accommodation to those touring on motorcycles.

Shoes & Slippers

Knowing which shoes to wear where in a Japanese inn can initially be very confusiong, but is a good thing to learn early on. Seeing gaijin take off their shoes as they arive reassures the inn-keeper that they know what they’re doing and will not make some truly awful faux pas like using soap in the bath.

When you enter a traditional inn there will be a genkan, a step up from street level, where you remove your shoes and put on slippers. There will usually be a series of pigeonholes where your shoes are stored and a large basket of assorted size slippers for you to select from. In the evening, the slippers will be lined up along the step, waiting for returning guests and new arrivals. In the morning, the process is reversed and guests’ shoes will be lined up on the street side of the step. The sight of large numbers of waiting slippers is a good clue that an otherwise unidentified (in English at least) building is actually an inn of some type.

Wearing the slippers, you can now proceed to your room but must remove them again at the door, or on a small standing area just inside your room. You now go barefoot or in socks on the tatami matting which covers the floor. Further complications await if you head for the toilet, as there’ll be another pair of slippers just inside the door for use only in that room. Toilet slippers are usually some garish color, making it immediately obvious that you have committed a grave misdeed if you forget to change back to the regular slippers afterwards!

Shoes outside, slippers inside, bare or socked feet in your room and toilet slippers in the toilet still does not encompass all the possibilities. Some inns will provide wooden sandals or the traditional geta sandals at the front door so you can make short trips out of the inn without having to own your own shoes. In onsen (spa towns) or other holiday centres many guests will, after their evening bath, wander the town wearing their yukata (cotton robes) but shoes simply do not look right with a yukata; geta are far more appropriate. If there’s a garden to wander in, yet another pair of sandals for that area may be awaiting you.

The Japanese Bath

The Japanese bath is another ritual which has to be learnt at an early stage and, like so many other things in Japan, is initially confusing but quickly becomes second nature. The all-important rule for using a Japanese bath is that you wash outside the bath and use the bath itself purely for soaking. Getting into a bath unwashed, or equally dreadful, without rinsing all the soap off your body, would be a major error.

One takes a bath in the evening, before dinner; a pre-breakfast bath is thought of a distinctly strange. In a traditional innthere’s no possibility of missing bath time, you will be clearly told when it’s time to head for o-furo (the bath) lest you not be washed in time for dinner! In a traditional in or a public bath, the bathing facilities will either be communal but sex segregated, or there will be smaller family bathing facilities for families or couples.

Take off your yukata or clothes in the ante-room to the bath and place them in the baskets provided. The bathrooms has taps, plastic tubs (wooden ones in very traditional places) and stools along the wall. Draw up a stool to a set of tapes and fill the tub from the taps or use it to scoop some water out of the bath itself. Sit on the stool and soap yourself. Rinse thoroughly so there’s no soap or shampoo left on you, then you are ready to climb into the bath. Soak as long as you can stand the heat, then leave the bath, rinse yourself off again, dry off and don your yukata.

FOOD IN JAPAN

Unlike Japanese restaurants in the West, Japanese restaurants in Japan tend to specialise in a particualr kind of dish or cuisine. The following sections describe some of the restaurants and dishes you are likely to encounter in Japan.

Okonomiyaki

This is an inexpensive Japanese cuisine, somewhat like a pancake or omelette with anything that’s lying around in the kitchen thrown in. The dish is usually prepared by the diner on a hotplate on the table. Typical ingredients include vegetables, pork, beef and prawns.

Ramen

This is a Chinese cuisine that has been taken over by the Japanese and made their own. These restaurants are generally the cheapest places to fill yourself up in Japan. Raman dishes are big bowls for noodles in a chicken stock with vegetables and or meat and are priced from around Y350 upwards.

Udon

This Osaka dish is similar to soba, except that the noodles are white and thicker.

Sukiyaki & Shabu-Shabu

Restaurants usually specialize in both these dishes. Sukiyaki is generally cooked on the table in front of the diner. It is prepared by cooking thinly sliced beef, vegetables and tofu in a slightly sweetened soya sauce broth. The difference between sukiyaki and shabu-shabu is in the broth that is used. Shabu-shabu is made with a stock-based broth.

Sushi & Sashimi

These are probably the most famous of Japanese dishes. The difference between them is that sashimi is thin sliver of raw fish served with soy sauce and wasabi (hot horseradish), while for sushi, the raw fish is set atop a small pillow of lightly vinegared rice.

Tempura

This dish has controversial origins, some maintaining that it is a Portuguese import. Tempura is what fish & chips might have been - fluffy, non-greasy batter and delicate, melt-in-your mouth portions of fish, prawns and vegetables.

Yakitori

Various parts of the chicken, skewered on a stick and cooked over a charcoal fire. Yakitori is great drinking food and the restaurants will serve beer and sake with the food.

Robatayaki

Robatayaki restaurants are celebrated as the noisiest in the world. Enter and you will be hailed by a chorus of welcoming irasshaimases , as if you were some long-lost relative. Orders are made by shouting. The food, a variety of things including seafood, tofu, and vegetables, is cooked over a grill. Again, this is a drinking cuisine. Both sashimi and yakitori are popular robatayaki dishes.

Nabemono

This winter cuisine consists of a stew cooked in a heavy earthenware pot.

Like sukiyaki, it is a dish cooked on the table in front of the diner.

Fugu

Only the Japanese could make a culinary specialty out of a dish which could kill you. The fugu, pufferfish or globefish, puffs itself up into an almost spherical shape to deter is enemies. Its delicate flesh is highly esteemed and traditionally served in carefully arranged fans of thinly sliced segments. Eat the wrong part of the humble pufferfish, however, and you drop dead. It’s said a slight numbness of the lips indicates you were close to the most exciting meal of you life but fugu fish chefs are carefully licensed, and losing customers is not encouraged. Every year there are a few deaths from pufferfish poisoning but they’re usually from home-prepared fish. Fugu can only be eaten for a few moths each year and the very best fugu restaurants, places which stecialize in nothing else, close down fro the rest of the year. It’s said that the fugu chef who loses a customer is honour bound to take his own life.

Unagi

This is Japanese for ‘eel’. Cooked Japanese style, over hot coals and brushed with soy sauce and sweet sake, this is a popular and delicious dish.

Kaiseki

The origins of kaiseki are in the tea ceremony, where a number of light and aesthetically prepared morsels would accompany the proceedings. True kaiseki is very expensive - the diner is paying for the whole experience, the traditional setting and so on.

Etiquette

When it comes to eating in Japan, there are quite a number of implicit rules, but they’re fairly easy to remember. If you’re worried about putting your foot in it, relax - the Japanese almost expect foreigners to make fools of themselves in formal situations and are unlikely to be offended as long as you follow the standard of politeness of your own country.

Among the more important eating ‘rules’ are those regarding chopsticks. Sticking them upright in you rice is considered very bad form, that’s how rice is offered to the dead! So is passing food from you chopsticks to someone else’s - another Buddhist death rite involves passing the bones of the cremated deceased amongst members of the family using chopsticks.

When eating with other people. The general practice is to preface actually digging into the food with the expression itadakimasu, literally ‘I will receive’. Similarly, at the end of the meal someone will probably say gochisosama deshita, a respectful way of saying that the meal was good and satisfying. When it comes to drinking, remember that you’re expected to keep

The Bento

This is the traditional Japanese box lunch, available for takeout everywhere, and usually comparatively inexpensive. It can be purchased in the morning to be taken along and eaten later, either outdoors or on the train as you travel between cities. The bento consists of rice, pickles, grilled fish or meat, and vegetables, in an almost limitless variety of combinations to suit the season.

The basement levels of most major department stores sell beautifully prepared bento to go. In fact, a department-store-basement is a great place to sample and purchase the whole range of foods offered in Japan:

Among the things available are French bread, imported cheeses, traditional bean cakes, chocolate bonbons, barbecued chicken, grilled eel, roasted peanuts, fresh vegetables, potato salads, pickled bamboo shoots, and smoked salmon.

The o-bento (the "o" is honorific) in its most elaborate incarnation is served in gorgeous, multilayered lacquered boxes as an accompaniment to outdoor tea ceremonies or for flower-viewing parties held in spring. Exquisite bento-bako (lunch boxes) made in the Edo period (1603-1868) can be found in museums and antiques shops. They are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and delicately hand-painted in gold. A wide variety of sizes and shapes of bento boxes are still handmade in major cities and small villages throughout Japan in both formal and informal styles. They make excellent souvenirs.

A major benefit to the bento is its portability. Sightseeing can take you down many an unexpected path, and you need not worry about finding an appropriate place to stop for a bite to eat-if you bring your own bento. No Japanese family would ever be without one tucked carefully inside their rucksacks right beside the thermos bottle of tea on a cross-country train trip. If they do somehow run out of time to prepare one in advance-no problem-there are hundreds of wonderful options in the form of the beloved eki-ben ("train station box lunches").

Each whistle-stop in Japan takes great pride in the uniqueness and flavor of the special box lunches, featuring the local delicacy, sold right at the station or fromvendors inside the trains. The pursuit of the eki-ben has become a national pastime in this nation in love with its trains. Entire books have been written in Japanese explaining the features of every different eki-ben available along the 26,000 km (16,120 mi.) of railways in the country. This is one of the best ways to sample the different styles of regional cooling in Japan and is highly recommended to any traveler who plans to spend time on the Japan Railway trains.

Soba and Udon

Soba and udon (noodle) dishes are another life-saving treat for stomachs (and wallets) unaccustomed to exotic flavors (and prices). Small shops serving soba (thin, brown buckwheat noodle) and udon (thick, white-wheat noodle) dishes in a variety of combinations can be found in every neighborhood in the country. Both can be ordered plain (ask for osoba or (o-udon), in a lightly seasoned broth flavored with bonito and soy sauce, or in combination with things like tempura shrimp ( tempura soba or udon) or chicken ( tori-namba soba or udon). For a refreshing change in summer, try zaru soba, cold noodles to be dipped in a tangy soy sauce. Nabeyaki-udon is a hearty winter dish of udon noodles, assorted vegetables, and egg served in the pot in which it was cooked.

Robatayaki. Perhaps the most exuberant of inexpensive options, is the robatayaki ( grill). Beer mug in hand, elbow-to-elbow at the counter of one of these popular neighborhood grills- that is the best way to relax and join in with the local fun. You’ll find no pretenses here, just a wide variety of plain, good food( as much or as little as you want) with the proper amount of alcohol to get things rolling.

Robata means fireside, and the style of cooking is reminiscent of old-fashioned Japanese farmhouse meals cooked over a charcoal fire in an open hearth. It’s easy to order at a robatayaki shop, because the selection of food to be grilled is lined up behind glass at the counter. Fish, meat, vegetables, tofu-take your pick. Some popular choices are yaki-zakana ( grilled fish), particularly Karei-shio-yaki ( salted and grilled flounder) ans asari saka-mushi (clams simmered in sake, Japanese rice wine). Try the grilled Japanese shiitake (mushrooms), ae-to (green peppers), and the hiyayakko( chilled tofu sprinkled with bonito flakes, diced green onions, and soy sauce). Yakitori can be ordered in most robatayaki shops, though many inexpensive drinking places specialized in this popular barbecued chicken dish.

The budget dining possibilities in Japan don’t stop them. Okonomiyaki is another choice. Somewhat misleadingly called the Japanese pancake, it is actually a mixture of vegetables, meat, and seafood in an egg-and-flour batter grilled at your table, much better with beer than with butter. It's most popular for lunch or as an after-movie snack.

|

|

|